http://myemail.constantcontact.com/...-Fall.html?soid=1114009586911&aid=9ymLXDgt8bI

A once-promising strategy for stability in Afghanistan ended badly two years ago, along with the career of its author and chief proponent, Army Special Forces Maj. Jim Gant. His gripping story is detailed in a new book, American Spartan, by Ann Scott Tyson, the former Washington Post war correspondent who interviewed him for anadmiring story in late 2009. They fell in love. Tyson eventually joined Gant in an Afghan village, where he built a reputation mobilizing local tribes against the Taliban.

A tough, wiry Special Forces soldier, Gant was decorated and recommended for promotion over 22 continuous months of combat in Afghanistan in 2010 and 2011. But in the end, the iconoclasm and disdain for military protocol that enabled Gant's success were instrumental in his eventual downfall.

At his peak, Gant, now 46, posed such a threat to al Qaeda's objectives that Osama bin Laden personally demanded his head, Tyson writes. Gant's lows came later, when he was accused by the military command of drinking and other violations, including keeping a "paramour," and using tactics that recklessly endangered the lives of his troops. At the heart of the military's discomfort, Gant believes, was his insistence that he could trust his life, and those of his men, to the tribal Afghan fighters he'd trained and armed to reverse the Taliban's spread across eastern Afghanistan.

To reach these tribes, Gant took a few seasoned Special Forces warriors "downrange," deep into rural communities where the Taliban held sway. He spent hours drinking tea and listening to village elders. He and his men grew beards. They wore Afghan clothing and learned to speak Pashto. They trained and armed village tribesmen and pledged their lives to one another. In the nonconformist tradition of the Green Berets, Gant shrugged away the U.S. military bureaucracy, with its thickets of regulations, codified as official Tactics, Techniques and Procedures. Among them: rules for specific combat operations that dictate the number of troops, types of vehicles and types of weapons used -- requirements often ignored by Special Forces teams, and especially by Gant.

Soon, Gant's teams of Green Berets and Afghans -- the beginning of what is known today as the Afghan Local Police (ALP) -- were operating against the Taliban together. His methods were risky -- Gant said he once drove with his team into a Taliban stronghold, dared them to attack, then stole their white flag when they refused. Sometimes, he said, he convinced Taliban fighters to join the local forces.

In Afghanistan, commanders allowed him the unusual freedom to operate as he saw fit. He was considered by then-Gen. David Petraeus and other top military commanders to be one of the leading counterinsurgency experts in the American military.

But his unconventional tactics and flouting of the rules eventually proved too much. In the spring of 2012, Gant was abruptly fired, stripped of his prized Special Forces insignia and forced into humiliating retirement. His work fell into disrepair.

Gant and Tyson, now married, expanded on their story in hours of exclusive interviews with The Huffington Post.

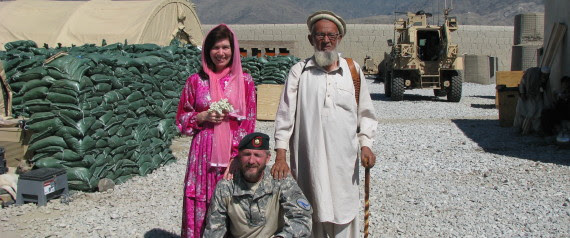

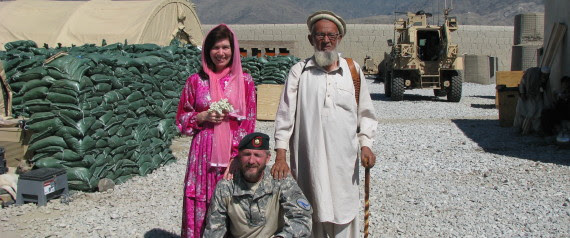

Journalist Ann Scott Tyson and Special Forces Maj. Jim Gant (front), in eastern Afghanistan in 2012.

Gant's introduction to Afghanistan came in 2003 and 2004, when he led a hunter-killer team and began to develop his ideas on arming and fighting alongside local tribes against the Taliban. He was sent next to Iraq, where he served two bloody tours, leading a U.S.-Iraqi commando team. Gant was awarded the prestigious Silver Star for gallantry in action, after an extended firefight in which he deliberately drove over and detonated three IEDs to protect his troops behind him. Back in the states as a Special Forces instructor, he began to realize that the killing wasn't working.

"I am in a group of outliers that really, really, really enjoyed combat, to include killing -- to hunt another human being down and shoot him in the face," Gant told me. "But if all you're doing is killing, and you're not gaining security, something is wrong. You have to relook [at] what it is that you're doing."

"War is not passing out candy," Gant said. "You're gonna have to kill. But ... at some point you have to do something different."

He knew that local tribes were Afghanistan's political, cultural and social center, built on intense loyalty to brother warriors, family and village, and a willingness to die to protect them from outsiders -- Taliban, Americans or the central government in Kabul. The tribal fighters offered, and demanded, respect, loyalty and honor.

Rather than propping up a weak and corrupt central government, Gant thought, the U.S. should be working bottom up: building trust with the tribes, then providing the pay and weapons for their own self-defense.

It was a bold concept. He detailed it in a paper, "One Tribe at a Time," which went online in the fall of 2009. The idea of using local manpower for security had been around for a while, but without a champion. Gant's proposal was an immediate hit in Washington: the Obama administration was searching for a way to win the war it had inherited in Afghanistan.

Pentagon brass were pressing for huge troop reinforcements. But Gant was pushing a low-cost and speedy solution, using Special Forces teams of Green Berets.

"In a situation where you're working feverishly to accelerate the development of the host nation capabilities -- and we knew there was a limited amount of time -- we had to get on with it, and this was one of the few ways we could get on with it," said a former senior commander in Afghanistan. He spoke on condition that he not be identified because of the lingering official sensitivity about Gant's career.

Inserting small Green Beret teams deep into remote villages, far from reinforcements, would be risky, Gant realized. "American soldiers would die, some of them alone, with no support," he wrote in the paper. "Some may simply disappear. Everyone has to understand that from the outset."

But, he observed, "We are losing in Afghanistan."

His ideas caught the attention of two powerful four-star officers: Adm. Eric Olson, then head of the Special Operations Command, and Gen. David Petraeus, then commander of U.S. Central Command. In short order, Gant was back in Afghanistan to put his ideas into action in June 2010.

Working in insurgent-controlled valleys in Konar Province, Gant and his teams of American and Afghan fighters operated far beyond the reach of reinforcements or air support. Their own security: absolute trust that each would fight to the death for the others.

Tyson went with them. She took a leave of absence from The Washington Post in September 2010, and flew to Afghanistan, where she gathered material for the book. Under Gant's supervision, Tyson learned to fire "almost every weapon" the Special Forces team used, she writes. On missions with Gant and his team, she wore U.S. military fatigues and tucked her hair up under a ballcap. Her job in a firefight was to pass ammunition to the turret gunner.

They'd visit villages and listen respectfully to the elders' ideas -- a time-consuming tactic not always practiced by other American soldiers. Gant's own personality evidently pleased Afghan villagers: polite, engaging and a careful listener, he values honor above all else, and is quick to bestow his friendship and trust -- but equally quick to erupt in violence if warranted.

"They knew, from back in '03 and '04, that I had smoked a lot of people. And they knew I'd burn the whole frickin' place down," Gant said. "But I'd also tell them, 'Hey -- I did not come to fight this time,' and I think that resonated with them."

Inevitably, they would encounter villagers who were fighting for the Taliban, and they'd talk. "I was more interested -- much more interested -- in talking to the Taliban than killing them," Gant said. On one mission, Gant and his men fought alongside an Afghan who had previously been a top Taliban commander. Like other defectors, his priority was to protect his home village turf, not to be part of an ideological movement directed from Pakistan.

Soon, officially sanctioned ALP units were forming across the country. In eastern Afghanistan by mid-2011, Gant and his teams had built ALP forces numbering some 1,300, up from zero the previous year, according to an official review in June 2011. Petraeus, then the senior military commander in Afghanistan, helicoptered in to award Gant an Army commendation medal for "exceptionally meritorious achievement" that enabled "the unprecedented advancement of the campaign in Afghanistan," the award citation states.

But trouble was brewing. Afghan President Hamid Karzai, concerned at the growing political clout of ALP commanders, seized control of the program and the U.S.-funded supplies for the ALP. Inevitably, Tyson writes, pay, fuel and ammunition intended for ALP units began to disappear inside the corrupt Afghan logistics system. Critics charged that the program was merely empowering vicious and untrustworthy warlords. There were accusations against some ALP units for human rights abuses.

and the U.S.-funded supplies for the ALP. Inevitably, Tyson writes, pay, fuel and ammunition intended for ALP units began to disappear inside the corrupt Afghan logistics system. Critics charged that the program was merely empowering vicious and untrustworthy warlords. There were accusations against some ALP units for human rights abuses.

The Special Forces command in Afghanistan, which often brought visiting brass and congressional delegations to admire Gant's operations, began to chafe at his bending of the rules, according to Tyson's account. Command started investigating Gant's lifestyle and his habit of thumbing his nose at official regulations, Tyson writes, including a prohibition on drinking and possession of painkillers, sleeping pills and other pharmaceuticals. He was accused of keeping a "paramour," a reference to Tyson. While their living arrangement was unusual, they argue in the book that her presence was a useful link to village women and helped cement ties between the Americans and the Afghans.

Gant also kept classified material in his room; it should have been kept "in a General Services Administration-approved security container and placed under continuous (i.e., 24/7) control by U.S. government personnel," according to a statement by the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC). To no avail, Gant responded to command that he kept drugs as the acting medic for his troops, and that there was nowhere else to store classified papers.

Asked whether it was common for Special Forces soldiers living in austere combat outposts to have access to alcohol, a USASOC spokesman, Lt. Col. Dave Connolly, wrote in a carefully worded email that soldiers are expected to obey the prohibition on alcohol and "are aware of the ramifications if caught."

Things got worse. Petraeus and other senior commanders who had supported Gant had gone home, Petraeus to take over the CIA. The commanders who remained, Gant said, resented his breaching of regulations and high-profile successes. On the basis of what Gant considers trumped-up charges of drinking, keeping drugs, living with Tyson and endangering the lives of his men due to his disregard for standard military procedure, in March 2012, Gant was plucked from his American and Afghan team and flown back to the states, where he received a severe, career-ending reprimand from Lt. Gen. John F. Mulholland, commander of the Army Special Operations Command. In a letter dated July 2012, Mulholland acknowledged Gant's "record of honorable and valorous service." But he said Gant's conduct had been "inexcusable and brought disrepute and shame to the Special Forces" and "disgraced you as an officer and seriously compromised your character as a gentleman."

The village where Gant had based his operations was abandoned by the U.S. command.

Maj. Gant was demoted a rank, to captain, and then allowed to retire. His security clearances were revoked. But what stung the most, he said, was the humiliation and betrayal of the trust he'd built with the Afghans, and his repudiation by senior Special Operations commanders, of whom he speaks bitterly. He feels he was railroaded out of the Green Berets by officers who valued by-the-book military procedure over successful warfighting.

"Yes, I broke those rules and I never say I didn't," Gant said, acknowledging that he drank and used sleeping pills and pain medication. "But I mean, we're not talking rape, murder, stealing property. I went to the extremes to protect my men. I loved them every day. I never lost a man. I'm proud. I can look in the mirror. If I went back and did it again, not one thing would I change."

Mulholland, now head of the U.S. Special Operations Command, declined to comment, through a spokesman.

Gant's work, while controversial, is still held as exemplary in many parts of the military. His operations "played a pivotal role in stabilizing .... an area that until very recently was under insurgent control," a superior wrote in June 2011. "His unprecedented success ... has had a strategic impact on our operations in Afghanistan."

"We needed Special Forces to be intrepid, to take risks, to feel that some rules didn't apply to them," the former senior commander in Afghanistan told me. "His strength, the strength of a lot of guys in those environments, was their willingness to push the envelope of the bureaucracy, to live with much less protection.

"But at the end of the day, it appears that he broke quite a few rules that shouldn't have been broken." Gant, this commander said, "felt he was exempt."

Thus was lost a promising initiative, one that might have matured into an inexpensive and self-sustaining movement to enable Afghans to help stabilize their own country. Gant's dramatic rise and fall calls into question whether even the Special Forces -- expected to excel in unconventional warfare -- can ever operate effectively in tricky conflicts like Afghanistan, where strict U.S. military procedures may not fit the environment or leave any room for rule-breaking mavericks.

In his 2009 paper, "One Tribe at a Time," Gant wrote that his gravest concern was that once his ideas were adopted and good relations were established with the Afghans, the U.S. would then abandon them and the ALP units. "By far the worst outcome we could have," he wrote, is that "the tribes to whom we have promised long-term support will be left to be massacred by a vengeful Taliban."

The latter has not happened, at least on a large scale.

Today in Afghanistan, there are close to 27,000 ALP in 29 of the country's 34 districts, according to Army Lt. Col James O. Gregory, a spokesman for the Special Operations Joint Task force in Afghanistan. But with the drawdown of U.S. troops and a withdrawal deadline at the end of this year, "few" Green Beret teams are embedded at the village level, Gregory said.

In cases where ALP positions have been overrun by the Taliban, Gregory wrote in an email, "they have the ability to call for direct assistance from neighboring [Afghan National Army] and [Afghan National Police] if needed."

A once-promising strategy for stability in Afghanistan ended badly two years ago, along with the career of its author and chief proponent, Army Special Forces Maj. Jim Gant. His gripping story is detailed in a new book, American Spartan, by Ann Scott Tyson, the former Washington Post war correspondent who interviewed him for anadmiring story in late 2009. They fell in love. Tyson eventually joined Gant in an Afghan village, where he built a reputation mobilizing local tribes against the Taliban.

A tough, wiry Special Forces soldier, Gant was decorated and recommended for promotion over 22 continuous months of combat in Afghanistan in 2010 and 2011. But in the end, the iconoclasm and disdain for military protocol that enabled Gant's success were instrumental in his eventual downfall.

At his peak, Gant, now 46, posed such a threat to al Qaeda's objectives that Osama bin Laden personally demanded his head, Tyson writes. Gant's lows came later, when he was accused by the military command of drinking and other violations, including keeping a "paramour," and using tactics that recklessly endangered the lives of his troops. At the heart of the military's discomfort, Gant believes, was his insistence that he could trust his life, and those of his men, to the tribal Afghan fighters he'd trained and armed to reverse the Taliban's spread across eastern Afghanistan.

To reach these tribes, Gant took a few seasoned Special Forces warriors "downrange," deep into rural communities where the Taliban held sway. He spent hours drinking tea and listening to village elders. He and his men grew beards. They wore Afghan clothing and learned to speak Pashto. They trained and armed village tribesmen and pledged their lives to one another. In the nonconformist tradition of the Green Berets, Gant shrugged away the U.S. military bureaucracy, with its thickets of regulations, codified as official Tactics, Techniques and Procedures. Among them: rules for specific combat operations that dictate the number of troops, types of vehicles and types of weapons used -- requirements often ignored by Special Forces teams, and especially by Gant.

Soon, Gant's teams of Green Berets and Afghans -- the beginning of what is known today as the Afghan Local Police (ALP) -- were operating against the Taliban together. His methods were risky -- Gant said he once drove with his team into a Taliban stronghold, dared them to attack, then stole their white flag when they refused. Sometimes, he said, he convinced Taliban fighters to join the local forces.

In Afghanistan, commanders allowed him the unusual freedom to operate as he saw fit. He was considered by then-Gen. David Petraeus and other top military commanders to be one of the leading counterinsurgency experts in the American military.

But his unconventional tactics and flouting of the rules eventually proved too much. In the spring of 2012, Gant was abruptly fired, stripped of his prized Special Forces insignia and forced into humiliating retirement. His work fell into disrepair.

Gant and Tyson, now married, expanded on their story in hours of exclusive interviews with The Huffington Post.

Journalist Ann Scott Tyson and Special Forces Maj. Jim Gant (front), in eastern Afghanistan in 2012.

Gant's introduction to Afghanistan came in 2003 and 2004, when he led a hunter-killer team and began to develop his ideas on arming and fighting alongside local tribes against the Taliban. He was sent next to Iraq, where he served two bloody tours, leading a U.S.-Iraqi commando team. Gant was awarded the prestigious Silver Star for gallantry in action, after an extended firefight in which he deliberately drove over and detonated three IEDs to protect his troops behind him. Back in the states as a Special Forces instructor, he began to realize that the killing wasn't working.

"I am in a group of outliers that really, really, really enjoyed combat, to include killing -- to hunt another human being down and shoot him in the face," Gant told me. "But if all you're doing is killing, and you're not gaining security, something is wrong. You have to relook [at] what it is that you're doing."

"War is not passing out candy," Gant said. "You're gonna have to kill. But ... at some point you have to do something different."

He knew that local tribes were Afghanistan's political, cultural and social center, built on intense loyalty to brother warriors, family and village, and a willingness to die to protect them from outsiders -- Taliban, Americans or the central government in Kabul. The tribal fighters offered, and demanded, respect, loyalty and honor.

Rather than propping up a weak and corrupt central government, Gant thought, the U.S. should be working bottom up: building trust with the tribes, then providing the pay and weapons for their own self-defense.

It was a bold concept. He detailed it in a paper, "One Tribe at a Time," which went online in the fall of 2009. The idea of using local manpower for security had been around for a while, but without a champion. Gant's proposal was an immediate hit in Washington: the Obama administration was searching for a way to win the war it had inherited in Afghanistan.

Pentagon brass were pressing for huge troop reinforcements. But Gant was pushing a low-cost and speedy solution, using Special Forces teams of Green Berets.

"In a situation where you're working feverishly to accelerate the development of the host nation capabilities -- and we knew there was a limited amount of time -- we had to get on with it, and this was one of the few ways we could get on with it," said a former senior commander in Afghanistan. He spoke on condition that he not be identified because of the lingering official sensitivity about Gant's career.

Inserting small Green Beret teams deep into remote villages, far from reinforcements, would be risky, Gant realized. "American soldiers would die, some of them alone, with no support," he wrote in the paper. "Some may simply disappear. Everyone has to understand that from the outset."

But, he observed, "We are losing in Afghanistan."

His ideas caught the attention of two powerful four-star officers: Adm. Eric Olson, then head of the Special Operations Command, and Gen. David Petraeus, then commander of U.S. Central Command. In short order, Gant was back in Afghanistan to put his ideas into action in June 2010.

Working in insurgent-controlled valleys in Konar Province, Gant and his teams of American and Afghan fighters operated far beyond the reach of reinforcements or air support. Their own security: absolute trust that each would fight to the death for the others.

Tyson went with them. She took a leave of absence from The Washington Post in September 2010, and flew to Afghanistan, where she gathered material for the book. Under Gant's supervision, Tyson learned to fire "almost every weapon" the Special Forces team used, she writes. On missions with Gant and his team, she wore U.S. military fatigues and tucked her hair up under a ballcap. Her job in a firefight was to pass ammunition to the turret gunner.

They'd visit villages and listen respectfully to the elders' ideas -- a time-consuming tactic not always practiced by other American soldiers. Gant's own personality evidently pleased Afghan villagers: polite, engaging and a careful listener, he values honor above all else, and is quick to bestow his friendship and trust -- but equally quick to erupt in violence if warranted.

"They knew, from back in '03 and '04, that I had smoked a lot of people. And they knew I'd burn the whole frickin' place down," Gant said. "But I'd also tell them, 'Hey -- I did not come to fight this time,' and I think that resonated with them."

Inevitably, they would encounter villagers who were fighting for the Taliban, and they'd talk. "I was more interested -- much more interested -- in talking to the Taliban than killing them," Gant said. On one mission, Gant and his men fought alongside an Afghan who had previously been a top Taliban commander. Like other defectors, his priority was to protect his home village turf, not to be part of an ideological movement directed from Pakistan.

Soon, officially sanctioned ALP units were forming across the country. In eastern Afghanistan by mid-2011, Gant and his teams had built ALP forces numbering some 1,300, up from zero the previous year, according to an official review in June 2011. Petraeus, then the senior military commander in Afghanistan, helicoptered in to award Gant an Army commendation medal for "exceptionally meritorious achievement" that enabled "the unprecedented advancement of the campaign in Afghanistan," the award citation states.

But trouble was brewing. Afghan President Hamid Karzai, concerned at the growing political clout of ALP commanders, seized control of the program

and the U.S.-funded supplies for the ALP. Inevitably, Tyson writes, pay, fuel and ammunition intended for ALP units began to disappear inside the corrupt Afghan logistics system. Critics charged that the program was merely empowering vicious and untrustworthy warlords. There were accusations against some ALP units for human rights abuses.

and the U.S.-funded supplies for the ALP. Inevitably, Tyson writes, pay, fuel and ammunition intended for ALP units began to disappear inside the corrupt Afghan logistics system. Critics charged that the program was merely empowering vicious and untrustworthy warlords. There were accusations against some ALP units for human rights abuses.The Special Forces command in Afghanistan, which often brought visiting brass and congressional delegations to admire Gant's operations, began to chafe at his bending of the rules, according to Tyson's account. Command started investigating Gant's lifestyle and his habit of thumbing his nose at official regulations, Tyson writes, including a prohibition on drinking and possession of painkillers, sleeping pills and other pharmaceuticals. He was accused of keeping a "paramour," a reference to Tyson. While their living arrangement was unusual, they argue in the book that her presence was a useful link to village women and helped cement ties between the Americans and the Afghans.

Gant also kept classified material in his room; it should have been kept "in a General Services Administration-approved security container and placed under continuous (i.e., 24/7) control by U.S. government personnel," according to a statement by the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC). To no avail, Gant responded to command that he kept drugs as the acting medic for his troops, and that there was nowhere else to store classified papers.

Asked whether it was common for Special Forces soldiers living in austere combat outposts to have access to alcohol, a USASOC spokesman, Lt. Col. Dave Connolly, wrote in a carefully worded email that soldiers are expected to obey the prohibition on alcohol and "are aware of the ramifications if caught."

Things got worse. Petraeus and other senior commanders who had supported Gant had gone home, Petraeus to take over the CIA. The commanders who remained, Gant said, resented his breaching of regulations and high-profile successes. On the basis of what Gant considers trumped-up charges of drinking, keeping drugs, living with Tyson and endangering the lives of his men due to his disregard for standard military procedure, in March 2012, Gant was plucked from his American and Afghan team and flown back to the states, where he received a severe, career-ending reprimand from Lt. Gen. John F. Mulholland, commander of the Army Special Operations Command. In a letter dated July 2012, Mulholland acknowledged Gant's "record of honorable and valorous service." But he said Gant's conduct had been "inexcusable and brought disrepute and shame to the Special Forces" and "disgraced you as an officer and seriously compromised your character as a gentleman."

The village where Gant had based his operations was abandoned by the U.S. command.

Maj. Gant was demoted a rank, to captain, and then allowed to retire. His security clearances were revoked. But what stung the most, he said, was the humiliation and betrayal of the trust he'd built with the Afghans, and his repudiation by senior Special Operations commanders, of whom he speaks bitterly. He feels he was railroaded out of the Green Berets by officers who valued by-the-book military procedure over successful warfighting.

"Yes, I broke those rules and I never say I didn't," Gant said, acknowledging that he drank and used sleeping pills and pain medication. "But I mean, we're not talking rape, murder, stealing property. I went to the extremes to protect my men. I loved them every day. I never lost a man. I'm proud. I can look in the mirror. If I went back and did it again, not one thing would I change."

Mulholland, now head of the U.S. Special Operations Command, declined to comment, through a spokesman.

Gant's work, while controversial, is still held as exemplary in many parts of the military. His operations "played a pivotal role in stabilizing .... an area that until very recently was under insurgent control," a superior wrote in June 2011. "His unprecedented success ... has had a strategic impact on our operations in Afghanistan."

"We needed Special Forces to be intrepid, to take risks, to feel that some rules didn't apply to them," the former senior commander in Afghanistan told me. "His strength, the strength of a lot of guys in those environments, was their willingness to push the envelope of the bureaucracy, to live with much less protection.

"But at the end of the day, it appears that he broke quite a few rules that shouldn't have been broken." Gant, this commander said, "felt he was exempt."

Thus was lost a promising initiative, one that might have matured into an inexpensive and self-sustaining movement to enable Afghans to help stabilize their own country. Gant's dramatic rise and fall calls into question whether even the Special Forces -- expected to excel in unconventional warfare -- can ever operate effectively in tricky conflicts like Afghanistan, where strict U.S. military procedures may not fit the environment or leave any room for rule-breaking mavericks.

In his 2009 paper, "One Tribe at a Time," Gant wrote that his gravest concern was that once his ideas were adopted and good relations were established with the Afghans, the U.S. would then abandon them and the ALP units. "By far the worst outcome we could have," he wrote, is that "the tribes to whom we have promised long-term support will be left to be massacred by a vengeful Taliban."

The latter has not happened, at least on a large scale.

Today in Afghanistan, there are close to 27,000 ALP in 29 of the country's 34 districts, according to Army Lt. Col James O. Gregory, a spokesman for the Special Operations Joint Task force in Afghanistan. But with the drawdown of U.S. troops and a withdrawal deadline at the end of this year, "few" Green Beret teams are embedded at the village level, Gregory said.

In cases where ALP positions have been overrun by the Taliban, Gregory wrote in an email, "they have the ability to call for direct assistance from neighboring [Afghan National Army] and [Afghan National Police] if needed."